By John Brady, Forest Historian

Uncovered by the glacial retreat some 15,000 years ago, the history of Black Rock Forest (BRF) and its people follows from an understanding of its geology, encompassing the minerals in billion-year-old granite gneisses, and its plants, borne of drought-prone, glacial till soils. Elevations of 400 to 1400 feet featured deep ravines with sparse flat fertile lands between many ridges and mountain peaks. The land, with its finicky climate, dictated and supports uniquely adapted plants, animals, and humans.

The first to make inroads, Native Americans, evidently entered the Hudson Highlands on footpaths running parallel to streambed ravines, including Mineral Springs, Canterbury, and Black Rock Brooks. The southern drainage of Cascade Brook through Glycerine Hollow led into an obvious forest of promise, a proven route to rock shelters, earthen clay sediments for making pottery, meat, nuts, berries, and a pleasant woodland diversion from Hudson River life.

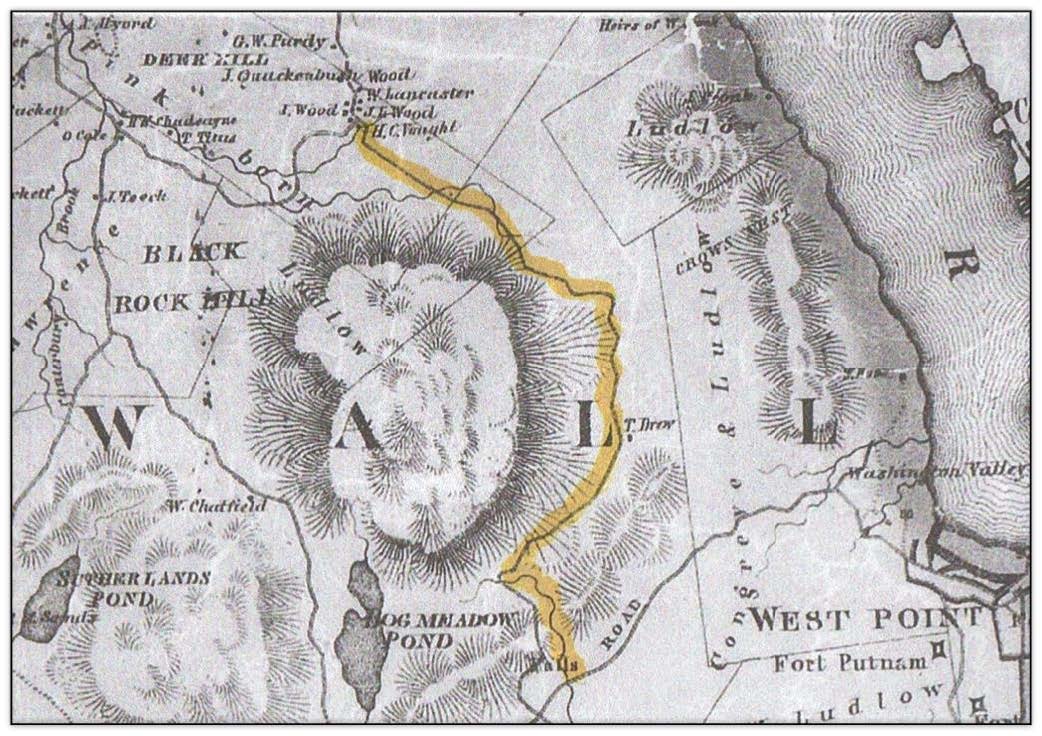

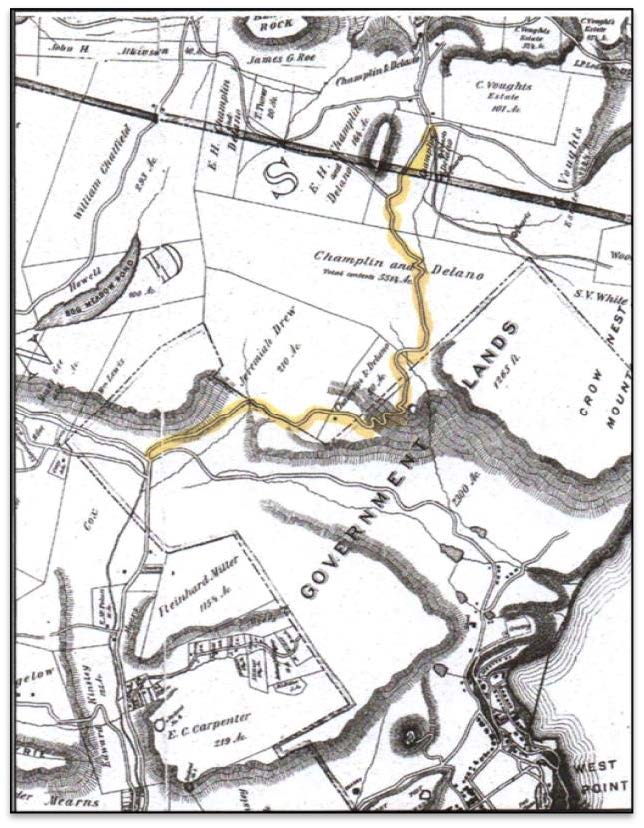

By the mid-1700s, European colonists looked upon the mountain forest as a warehouse of supply. A 1778-79 manuscript map drawn by Robert Erskine, George Washington’s map maker, confirms the initial road into present-day Black Rock Forest. The location of this early passage through the Highlands was quite possibly the primary land route of fleeing soldiers and militia after the fall of Forts Montgomery and Clinton on October 6, 1777. During the American Revolution era, the southern extensions of this road led to the “Forest of Dean” and Queensboro furnaces, six miles from Whitehorse Mountain and four miles from Glycerine Hollow. This roadbed called the “West Point and Cornwall Road” later known as the Ben Lancaster Path was abandoned with the construction of the close-by West Point Road (also known as the Esses Road) in 1872. These roads, considered usable as supply routes for wood and wood-charcoal, indicate the initial commercial cutting of Black Rock Forest trees. Today, in its abandoned state and now known as “Old West Point Road,” it is used only as a firebreak and has been replaced by Route 9W, built in 1941, as the primary road over the Hudson Highlands.

After the American Revolution, settlers arrived in the Black Rock Forest region from the neighboring hamlets of Cornwall Heights, Butterhill Clove, West Grove, Highland Mills and Ketchamtown. The names Drew, Avery, Lancaster, O’Dell, Chatfield, Babcock, Wood and Vought, Hall and Ryerson date back to the mountain farmers and hill people who worked the highlands, then known as Black Rock Hill.

In the early 1800s, the Hudson Highlands were supplying other wars with wood and iron–the War of 1812, and, later, the Civil War. The construction of the Continental Army Road in 1782 provided an additional supply route to the developing ironworks in the Ramapo region. With road access, squatters and landowners continued their conquest of wood and mineral resources. Small-scale agriculture took hold, providing fruit, grain, and meat, yielding self-sustaining commodities with surplus delivered to market at Cornwall Landing, the Mountain House, and other Highlands hotels. Wood and wood-charcoal were welcomed, both to fuel local iron and blacksmith furnaces, and to provide heat for townsfolk.

With the production of iron ore moving to the Midwest during the 1880s, coal replaced wood-charcoal. The local woodcutting industry continued to supply wood to local brickyards, glass and pottery manufacturers and communities.

By 1890, wealthy families of this era (Harriman, Rockefeller, and Stillman) became aware of these lands that viewed the great Hudson River from ancient mountains. Large acreages, presenting abused landscapes that had supported the country’s wars for independence, presented cheap investments in their abandoned states.

By 1900, the forest clearly showed the result of 150 years of tree cutting. The largest trees of 10– 12-inch diameter at breast height were now only found in remote, hard to reach terrain. The woodland was composed of dense, ill-formed stump sprouts of those sprout-capable species (e.g., oak, ash, hickory). Those species that reproduce by seed only had been seriously depleted (e.g., pine, spruce, hemlock). With the arrival of the chestnut blight in 1903, the forest became a dismal sight with up to 20% of forest trees dead. Wildlife was also diminished: rabbits, squirrels and woodchucks were the only common mammals.

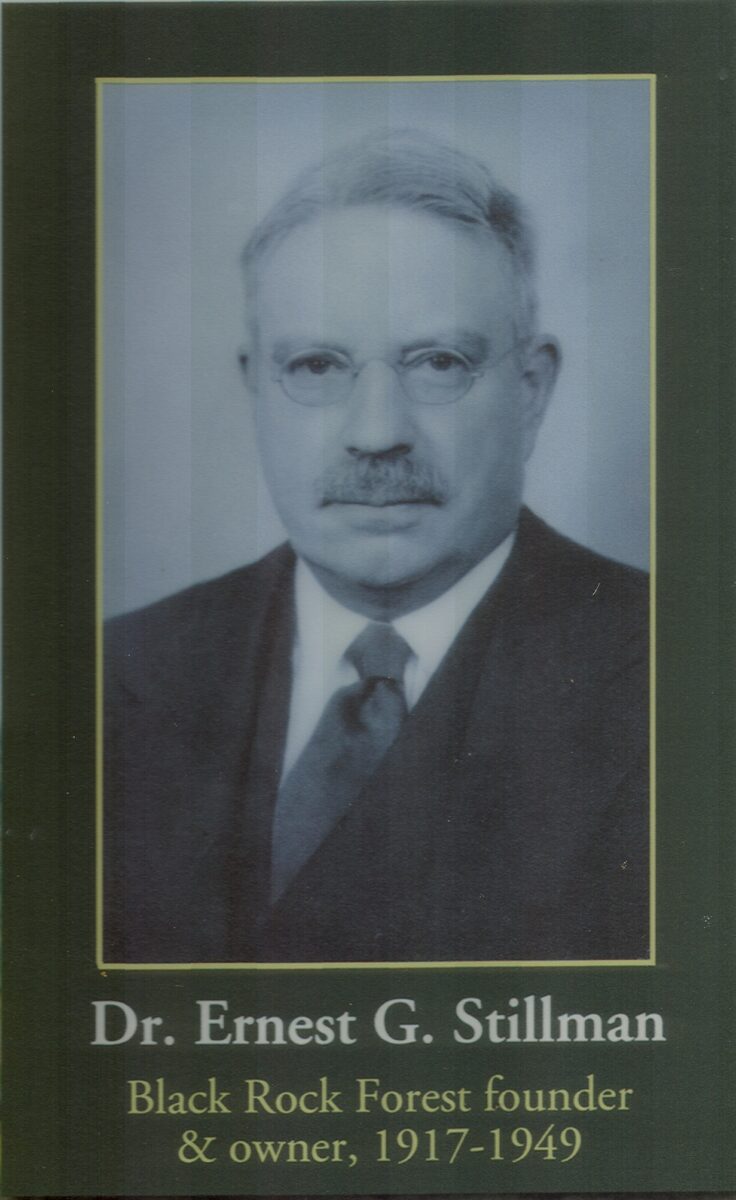

Enter James Stillman, considered to be the founder of National City Bank (Citibank). James dealt in land purchases while he was a regular visitor to his Cornwall estate (now known as Jogues Retreat), investing in a legacy to be realized by his son Ernest. Many settlers on the property departed during James Stillman’s time. He allowed his lands to be worked seasonally. Year-round farming ended with the abandoning of the Chatfield Place, which was gutted by fire in 1907, and after the large forest fire of 1911. In 1918, upon the death of his father, Dr. Ernest Stillman inherited vast acreages that included what would become Black Rock Forest.

Dr. Ernest Stillman, (1884-1949) being a Harvard man, (Class of 1907), looked to the University for guidance regarding the healing of a damaged mountain forest. In 1926, Richard Fisher (Class of 1898), Director of the Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts, walked the Black Rock woodlands with Dr. Stillman. Mr. Fisher was an advocate of the “Father of American Forestry,” Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot’s concept of forest management was to achieve a robust and self-sustaining state while continuing to support yields to supply human needs. Dr. Stillman, a physician of respiratory disease, certainly believed in a healthier environment that could be enjoyed by all. Experimental forestry was a young science that would allow him to pursue that vision. Fisher convinced Ernest to pursue the creation of a demonstration forest entitled, “Black Rock Forest”

Dr. Ernest Stillman, (1884-1949) being a Harvard man, (Class of 1907), looked to the University for guidance regarding the healing of a damaged mountain forest. In 1926, Richard Fisher (Class of 1898), Director of the Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts, walked the Black Rock woodlands with Dr. Stillman. Mr. Fisher was an advocate of the “Father of American Forestry,” Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot’s concept of forest management was to achieve a robust and self-sustaining state while continuing to support yields to supply human needs. Dr. Stillman, a physician of respiratory disease, certainly believed in a healthier environment that could be enjoyed by all. Experimental forestry was a young science that would allow him to pursue that vision. Fisher convinced Ernest to pursue the creation of a demonstration forest entitled, “Black Rock Forest”

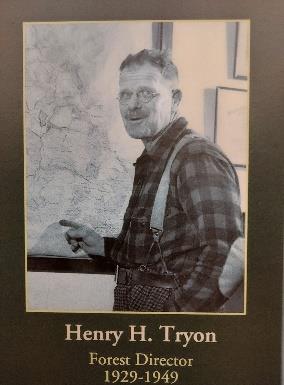

Henry H. Tryon, (1888-1953) also a Harvard man (Class of 1912), upon recommendation by Fisher, became the first director of Black Rock Forest in 1927. Tryon’s task was stated by Fisher: “…probably the first institution of its kind to be established in the United States, a private property organized as a forest laboratory for research in problems of forest management and for the demonstration of successful methods in practice.” Over the following twenty years Tryon would oversee the publication of numerous research bulletins and papers.

Henry H. Tryon, (1888-1953) also a Harvard man (Class of 1912), upon recommendation by Fisher, became the first director of Black Rock Forest in 1927. Tryon’s task was stated by Fisher: “…probably the first institution of its kind to be established in the United States, a private property organized as a forest laboratory for research in problems of forest management and for the demonstration of successful methods in practice.” Over the following twenty years Tryon would oversee the publication of numerous research bulletins and papers.

Knowledge of forest science and dynamics blossomed, as did the appearance and health of the forest. The successful work created a forest valued by everyone. The Black Rock Fish and Game Club patrolled forest lands, enforcing fire protection and stewardship values in exchange for hunting and fishing rights to the growing wildlife populations. Forest visitors were educated by these demonstrations of forest stewardship and became respectful advocates of the land.

At the height of forest management prosperity, Dr. Ernest Stillman died unexpectedly in 1949 at the age of 65 years. The forest, with endowment, was bequeathed to Harvard University, under the assumption that they would pursue and further these goals. Harvard saw things differently: “…the amount of research at Black Rock Forest is limited.” “We do not consider that Black Rock Forest is essential.” Their forty years of ownership (1949-1989) had few highlights except for the preservation and maturation of Stillman-Tryon’s managed forest and stewardship.

Enter William T. Golden, (1909-2007) Harvard Business School 1931, founder of the Black Rock Forest Consortium. Using persistence, influence and persuasion, Mr. Golden relieved Harvard of its forest burden. Since 1979, Mr. Golden had been diligently building a collection of schools and institutions to continue and enhance the forest legacy of Dr. Stillman. For the past thirty-three years, this forest has been the focus of, and forum for, proven and promising minds contemplating the intriguing potential that resides in BRF. The Consortium integrates the natural and human history of the forested land with modern educational and research methods and knowledge, working together to investigate and understand the wisdom of our natural world.

Enter William T. Golden, (1909-2007) Harvard Business School 1931, founder of the Black Rock Forest Consortium. Using persistence, influence and persuasion, Mr. Golden relieved Harvard of its forest burden. Since 1979, Mr. Golden had been diligently building a collection of schools and institutions to continue and enhance the forest legacy of Dr. Stillman. For the past thirty-three years, this forest has been the focus of, and forum for, proven and promising minds contemplating the intriguing potential that resides in BRF. The Consortium integrates the natural and human history of the forested land with modern educational and research methods and knowledge, working together to investigate and understand the wisdom of our natural world.