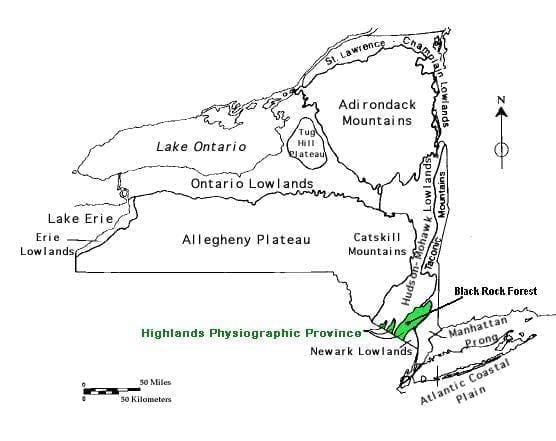

Black Rock Forest is located at the intersection of the Highlands Physiographic Province; (also known as the New York-New Jersey Highlands,) with the Hudson River Basin. Spy Rock summit in Black Rock Forest is the highest point in the Highlands west of the Hudson River, at 1461 feet above sea level.

The Highlands are underlain by Precambrian granites and gneisses more than one billion years old that have been extensively folded, faulted, and metamorphosed. These are the basement rocks of the Reading Prong Province, which stretches from eastern Pennsylvania for nearly 200 miles northeast to western Connecticut. The Hudson Highlands drop off dramatically for 1000 feet or more on all sides. The geologic province to the south comprises the Newark Basin Lowlands, composed of much younger and more easily eroded sedimentary rocks.

North of the Highlands lies the Great Valley, underlain by Paleozoic sedimentary rocks and comprising the first valley of the Ridge and Valley Province. Further to the north are more substantial mountain ranges, the Catskills and Adirondacks.

The most dramatic drop-offs in the Highlands occur where the Hudson River has cleft the range down below sea level, a little more than one mile east of Black Rock Forest. At the northern entrance to the Hudson River Gorge, between Storm King Mountain and Breakneck Ridge, the mountains rise more than 1300 feet above the river on both sides.

A series of three major geologic events uplifted New York State’s ancient rocks to create mountains which were subject to weathering and erosion after each mountain-building event. The first, 460-440 million years ago during the Ordovician period, was caused by a collision with an arc-shaped set of volcanic islands located east of North America (the Taconian Orogeny). This event was responsible for creation of the Highlands. The second event, during the Mississippian and Devonian periods (375 to 335 million years ago), was caused by a collision with a continent located east of North America (the Acadian Orogeny). The final event, about 250 million years ago during the Permian period (the Alleghanian Orogeny), was caused by a collision with West Africa that created the super continent Pangaea. About 200 million years ago, Pangaea began to split apart and form the continents we know today.

The Catskill and Adirondack Mountains to the north were also formed by these large events. The Hudson Highlands are considered stable bedrock because they have remained intact for such a long period of time.

The mountains, however, have been subject to erosion and glaciation in more recent times. The last glacial period ended about 12,000 years ago and is responsible for much of the current local topography. The ice sheet stretched from Canada down to Long Island and across what is now the Interstate 80 corridor in New Jersey, and carved valleys and scoured mountains as it moved. Some of the rocks and ground material it left as it retreated now cover the bedrock over much of the Forest, this material is known as glacial till.

The development of the Hudson River Basin, which ranges from northern New York and the Adirondacks down to the Atlantic, also played a role in forming the current topography of Black Rock Forest. The river itself and its tributaries, including Black Rock Brook, have been constantly carving away at the land, resulting in the landscape we see today.

Magnetite: the Black Rock of the Forest

Black Rock Forest’s gneiss bedrock is a metamorphic rock, composed of the minerals feldspar, quartz, amphibole, pyroxene, and mica. Feldspar and quartz are both lighter-colored minerals and are seen as white or gray bands in the rock. Hornblende, pyroxene, and some of the other minerals are dark and can be seen as black bands in the gneiss. There are many kinds of gneisses at the Forest, some of which contain the black mineral magnetite, for which the Forest was named.

Magnetite can be found scattered throughout the Forest. This “black rock” is an iron ore, characterized by a low melting point. During the 1700s and 1800s, iron was extracted from magnetite by heating rock in a furnace. The liquid iron was poured into molds and used to make guns, cannons, and the chain that stretched across the Hudson River during the Revolutionary War period, and continued to be used by foundries in the Highlands throughout the 1800s. Much of the ore was found south of the Forest near Bear Mountain and Harriman State Parks. However, Hudson Highlands magnetite was not exploited or mined as extensively as the higher-quality iron ore that was found in neighboring Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

One interesting attribute of magnetite is that, just as the name implies, it is magnetic. When magnetite is held near a compass, the compass needle swings away from true north, toward the locally stronger magnetic field of the rock. It is believed that the effect of magnetite deposits on cockpit instruments may have been partly responsible for two small plane wrecks that occurred in the 1960’s on Black Rock Forest’s Hill of Pines, which occurred within a few hundred yards of one another.

References

Denny, C.S. 1938. “Glacial geology of the Black Rock Forest,” Black Rock Forest Bulletin No. 8. Cornwall Press, Cornwall, NY. 70 p. Leger, A., C. Rebbert and J. Webster. 1996. “Cl-rich biotite and amphibole from Black Rock Forest, Cornwall, New York.” American Mineralogist 81: 495-504.